Using your MSDS/SDS to determine transport hazard classes

In the fast-paced world of international trade, air cargo is often the preferred mode of transport for high-value or time-sensitive goods. However, the movement of cargo is a competitive commercial business with considerable scope for error. Unlike a passenger who can complain if the cabin is too hot, cargo cannot speak; it cannot protest if it is misrouted, lacks proper documentation, or is labeled incorrectly.

For new exporters, procurement managers, and manufacturers, the most critical “voice” your cargo has is its documentation. Specifically, when dealing with chemical products or items with hazardous components, the Safety Data Sheet (SDS)-formerly known as the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS)-is your primary tool for ensuring safety.

Many manufacturers treat their products as “General Cargo” without realizing they contain components classified as hazardous by aviation authorities. Negligence or overlooking legislation can have a serious impact on property as well as on the safety and health of all concerned. This guide will walk you through using your SDS to identify Transport Hazard Classes and ensure your shipments are “Ready for Carriage”.

General Cargo vs. Dangerous Goods: What is the Difference?

Before diving into classification, it is essential to distinguish between the two main categories of air transport:

General Cargo refers to items that do not pose inherent risks during transport. These goods do not require special handling related to safety hazards, although they still require proper packaging to withstand normal transport conditions.

Dangerous Goods (DG), on the other hand, have a very specific definition. According to IATA, dangerous goods are articles or substances which are capable of posing a risk to health, safety, property, or the environment. These goods are governed by strict regulations found in the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR) manual, which must be followed by all IATA Member airlines and all shippers offering such consignments.

The Risk of “Hidden” Dangerous Goods

A major pitfall for new exporters is “Hidden Dangerous Goods.” These are substances and articles that do not seem to contain any dangerous items based on their general description but may nevertheless contain hazardous components.

Operators’ acceptance staff are trained to detect these, but the shipper is ultimately responsible. Common examples include:

- Dental Apparatus: May contain flammable resins, solvents, or mercury.

- Electrical Equipment: May contain magnetized materials, wet batteries, or lithium batteries.

- Automobile Parts: May contain engines with residual fuel, air bag inflators, or compressed gas shocks/struts.

- Pharmaceuticals: May contain radioactive material, flammable liquids, or oxidizers.

If you are shipping any item that might contain chemicals, batteries, or pressurized components, you must verify if it falls under one of the 9 Hazard Classes.

The 9 Classes of Dangerous Goods

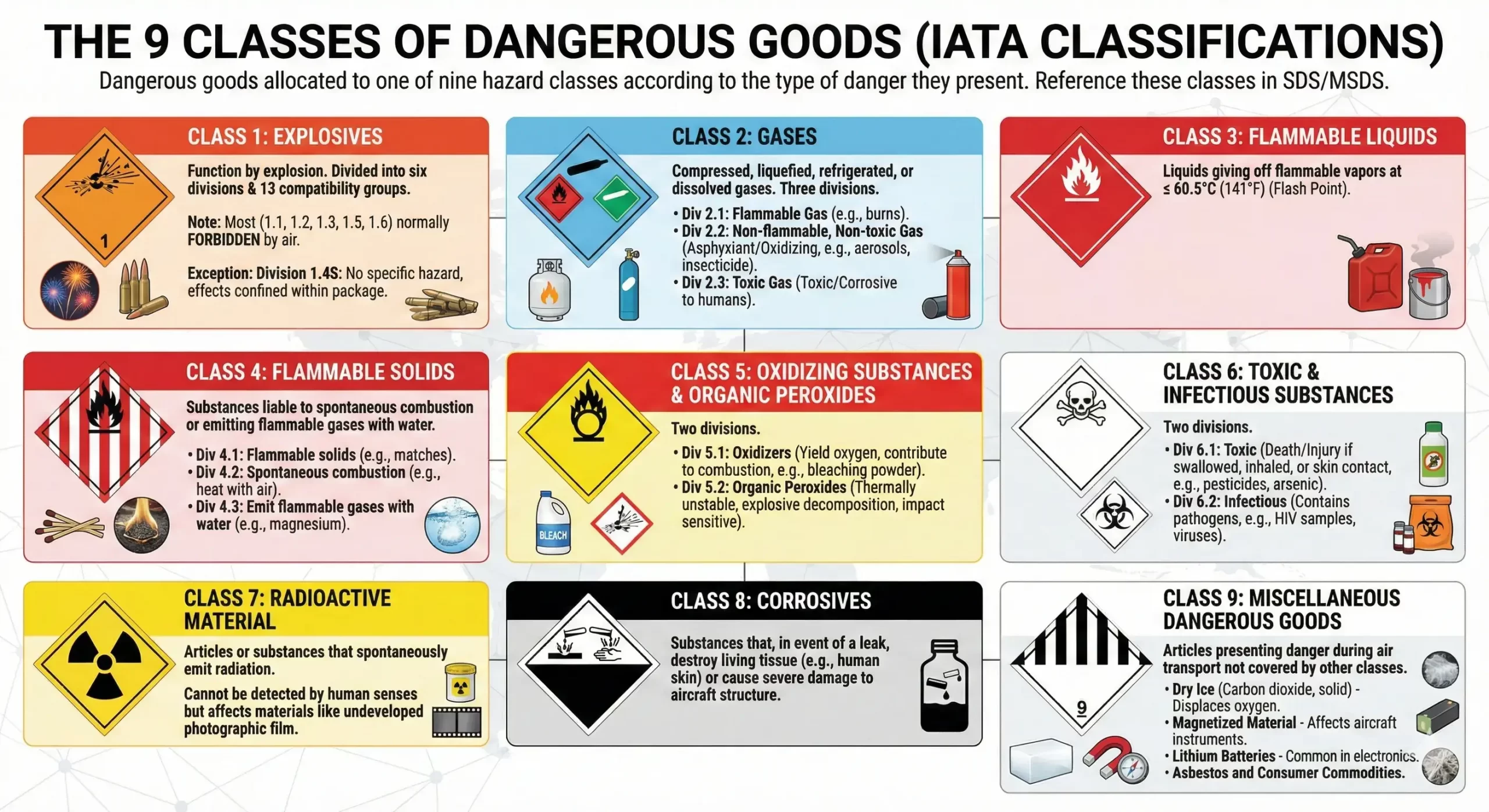

Dangerous goods are allocated to one of nine hazard classes according to the type of danger they present. Your SDS/MSDS will usually reference these classes.

Class 1: Explosives

This class is assigned to goods that function by explosion. They are divided into six divisions and 13 compatibility groups.

- Note: Most explosives (Divisions 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.5, and 1.6) are normally forbidden for carriage by air.

- Exception: Division 1.4S lists articles with no specific hazard where effects are confined within the package.

Class 2: Gases

This class covers compressed, liquefied, or refrigerated gases, or gases in solution. It is split into three divisions:

- Division 2.1 (Flammable Gas): Gases that will burn.

- Division 2.2 (Non-flammable, Non-toxic Gas): Gases that are asphyxiant or oxidizing, such as aerosols or insecticide gas.

- Division 2.3 (Toxic Gas): Gases known to be toxic or corrosive to humans.

Class 3: Flammable Liquids

To be classified here, a liquid must give off flammable vapors at temperatures of not more than 60.5°C (141°F) in a closed-cup test. This temperature threshold is known as the “flash point”. Common examples include paint and gasoline.

Class 4: Flammable Solids

This class includes substances liable to spontaneous combustion or those that emit flammable gases when in contact with water.

- Division 4.1: Flammable solids (e.g., “strike anywhere” matches).

- Division 4.2: Substances liable to spontaneous combustion (e.g., heating up when in contact with air).

- Division 4.3: Substances that emit flammable gases when in contact with water (e.g., magnesium powder).

Class 5: Oxidizing Substances and Organic Peroxides

- Division 5.1 (Oxidizers): Substances that yield oxygen and contribute to the combustion of other material (e.g., bleaching powder).

- Division 5.2 (Organic Peroxides): Thermally unstable substances liable to explosive decomposition or sensitive to impact.

Class 6: Toxic and Infectious Substances

- Division 6.1 (Toxic): Substances liable to cause death or injury if swallowed, inhaled, or contacted by skin (e.g., arsenic, pesticides).

- Division 6.2 (Infectious): Substances containing pathogens like viruses or bacteria (e.g., HIV samples for research).

Class 7: Radioactive Material

Articles or substances that spontaneously emit radiation. This radiation cannot be detected by human senses but can affect other materials like undeveloped photographic film.

Class 8: Corrosives

These are substances that, in the event of a leak, can destroy living tissue (such as human skin) or cause severe damage to the aircraft structure itself.

Class 9: Miscellaneous Dangerous Goods

This class covers articles that present a danger during air transport not covered by other classes. Examples include:

- Dry Ice (Carbon dioxide, solid): Used to cool foodstuffs but displaces oxygen in enclosed areas.

- Magnetized Material: Can affect aircraft instruments like the compass.

- Lithium Batteries: Increasingly common in electronics.

- Asbestos and Consumer Commodities.

How to Use Your MSDS/SDS to Classify Cargo

The Safety Data Sheet is the “passport” for your chemical cargo. To determine if your product is hazardous for air transport, follow these steps:

a. Locate Section 14: Transport Information

While an SDS has many sections regarding health and storage, Section 14 specifically addresses transport. Look for the “IATA” or “Air Transport” subsection.

b. Identify the UN Number

Dangerous goods are assigned a UN number to make worldwide communication possible.

- Example: “Dry Ice” is assigned UN 1845.

- Action: If your SDS lists a UN number, your product is likely regulated.

c. Verify the Proper Shipping Name

The UN number corresponds to a “Proper Shipping Name”. This is the standard technical name used on all transport documentation. For example, the proper name for Dry Ice is “Carbon dioxide, solid” or “Dry ice”.

d. Check the Packing Group

Some classes are assigned a Packing Group, which indicates the degree of danger presented by the substance. This will determine the type of packaging you must use.

- Packing Group I: High danger.

- Packing Group II: Medium danger.

- Packing Group III: Low danger.

e. Cross-Reference with IATA DGR

The SDS is the starting point, but the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR) manual is the legal source. You must check if the substance is forbidden on passenger aircraft (requiring a “Cargo Aircraft Only” label) or if there are specific quantity limitations.

The Shipper’s Responsibility

Classification and Documentation

It is the shipper’s responsibility to classify, identify, pack, mark, label, and document dangerous goods according to applicable regulations. Once the hazard is identified via the SDS, the shipper must complete the Shipper’s Declaration for Dangerous Goods (DGD).

- This document confirms the goods are accurately described and packed.

- It must be completed in English.

- It requires two original copies with original signatures (digital or typed signatures are generally not permissible on paper forms).

Mandatory Training

Any individual physically accepting, handling, arranging transportation for, or issuing documents for a shipment containing Dangerous Goods must have IATA DGR training.

- Initial Training: Required before handling any DG.

- Recurrent Training: Must occur within 24 months of the previous training to keep knowledge up to date.

Legal Consequences

An offence that can lead to fines or imprisonment may be committed if a shipper offers a consignment that does not comply with the IATA Dangerous Goods Regulations. The airline also faces penalties if they carry non-compliant shipments.

Conclusion

Classifying cargo correctly is not just about avoiding fines; it is about ensuring the safety of the aircraft, the crew, and everyone involved in the supply chain. Cargo that is misdeclared-whether intentionally or through ignorance-can cause fires, leakage, or structural damage to the aircraft. By using your MSDS/SDS and understanding the 9 Hazard Classes defined by IATA, you can ensure your shipments move smoothly and safely.

Next Step: Are you unsure if your current MSDS/SDS is up to date or how to interpret the Transport Information section? Contact our logistics experts today for a consultation on Dangerous Goods classification and air freight compliance.