Structure, categories & technical characteristics of cargo aircraft – core knowledge in logistics

In the rapid world of global commerce, air freight represents the pinnacle of speed and reliability. When critical shipments-from life-saving pharmaceuticals and high-value electronics to essential manufacturing parts-need to cross continents in hours, the cargo aircraft is the silent powerhouse making it happen.

However, moving goods by air is more complex than simply booking space. As a shipper, importer, or logistics professional, a core understanding of the cargo aircraft’s structure, capacity, and technical characteristics is not just academic knowledge-it is a competitive advantage. It directly impacts your cargo’s safety, the cost of your shipment, and the maximum dimensions you can ship.

This comprehensive guide, tailored for both seasoned logistics experts and newcomers, will unlock the technical fundamentals of the freighter aircraft, transforming a seemingly complex machine into an accessible concept that will help you optimize your air freight strategy.

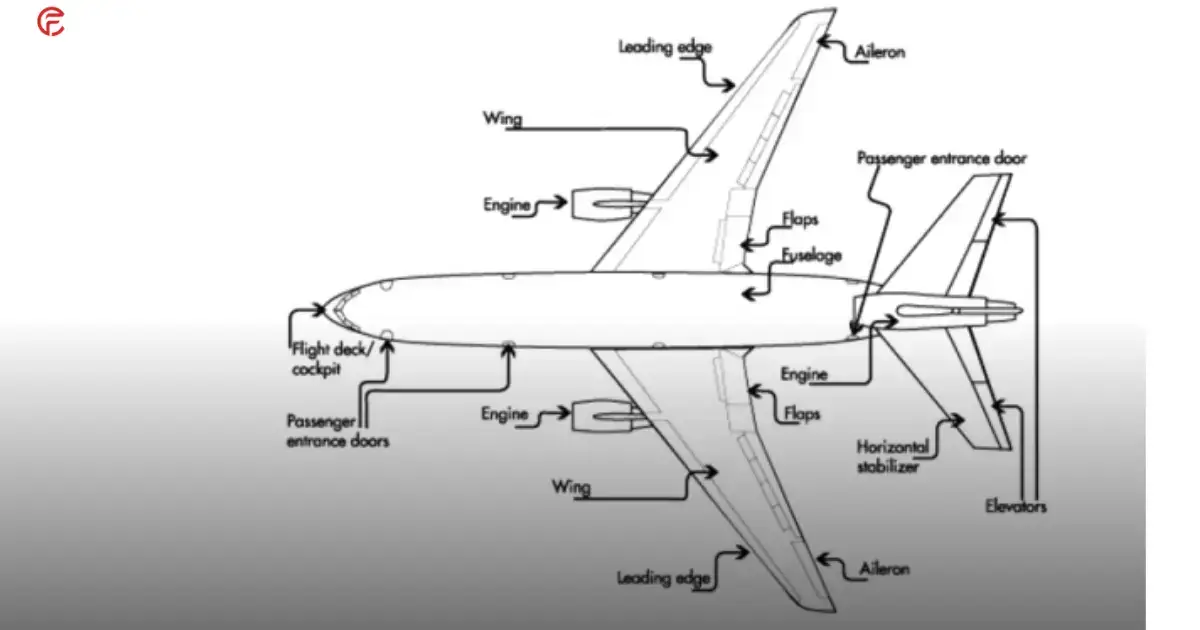

Aircraft Structure

Aircraft categories: narrow-body vs. wide-body freighters

Narrow-body (Single-Aisle)

- Characteristics: These are smaller aircraft with a single aisle down the center. Examples include the Boeing 737 Freighter or the Airbus A321 Freighter.

- Cargo Capacity: They typically carry cargo only in the lower deck (belly). The limited size means they cannot accommodate the largest ULD types (like the standard 88” x 125” pallets) on the main deck.

- Route Role: Ideal for short-haul or medium-haul domestic and regional routes, often feeding cargo into larger international hubs. Their capacity is limited, but their lower operational cost makes them efficient for specific markets.

Wide-body (Dual-Aisle)

- Characteristics: These are large, twin-aisle aircraft, designed for long-haul international travel. They include giants like the Boeing 747 Freighter (747-8F), Boeing 777 Freighter (777F), and the Airbus A330 Freighter.

- Cargo Capacity: These are the workhorses of global air freight. They can carry significant volume on both the main deck and the lower deck (belly). The main deck is sized to accept large, non-standard, or out-of-gauge cargo.

- Route Role: Essential for transcontinental routes, offering massive payload capabilities and the flexibility to carry specialized cargo, including temperature-sensitive goods and live animals, due to their advanced compartment control systems.

Detailed aircraft layout: understanding the cargo space

Main and Lower Deck (Deck vs. Hold)

- Main Deck: Located where passengers sit on a commercial plane. On a freighter, this is the primary area for cargo. It can accommodate the largest Unit Load Devices (ULDs) and often features a sophisticated automated loading system. It’s the area of choice for large, bulky, or out-of-gauge shipments.

- Lower Deck (Belly): Located beneath the main deck, this is also called the “belly hold” or “lower hold.” Even on a full-freighter, the lower deck is utilized. It is generally divided into compartments (Hold 1, Hold 2, etc.) and is used for smaller ULDs (like the LD3 container) or bulk cargo (loose packages).

Holds and Compartments

Aircraft cargo space is divided into designated areas called holds or compartments.

- Compartment Coding: Each hold has specific limitations regarding maximum weight, maximum height, and maximum ULD type. This information is meticulously documented by the airline and is crucial for planning.

- Specialized Compartments: Many wide-body aircraft have holds dedicated to carrying sensitive goods, such as “live animal” compartments with specific ventilation or temperature-controlled holds for pharmaceuticals (often part of a Certified Pharma program).

Cargo Doors: The Entry Point

The size and location of the cargo doors are arguably the most critical factor for shippers dealing with large or heavy items.

- Side Cargo Door: Found on the main deck of most freighters, these are significantly larger than passenger doors, allowing for the easy entry of full-size pallets.

- Nose Cargo Door (747F, 747-8F): The iconic 747 Freighter can lift its entire nose section, creating an enormous opening. This is essential for loading extremely long or tall items, such as oil drilling equipment, satellite components, or oversized vehicles. If your cargo is taller than 96 inches, you will likely require an aircraft with a nose door.

Tie-Down: Securing the Shipment

During flight, cargo must withstand significant G-forces from acceleration, deceleration, and turbulence. The tie-down system is non-negotiable for safety.

- Floor Locks and Restraints: The aircraft floor is equipped with an array of locks that secure ULDs directly to the airframe.

- Nets, Straps, and Chains: Loose cargo or items that cannot fit perfectly onto a ULD are secured using nets, heavy-duty straps, or chains attached to the designated tie-down points (rings) on the floor. Proper tie-down ensures that the cargo remains stationary, preventing damage to the goods, the aircraft, and guaranteeing a safe flight.

Pressurization and Temperature Control

Unlike sea freight, air cargo operates at extremely high altitudes where outside temperatures can drop to -50°C.

- Pressurization: The cargo holds are pressurized (though less than the flight deck and passenger area) to ensure that packaging does not rupture and that liquids or sensitive items are protected.

- Temperature Control: For perishable goods (PER), fresh produce (FRG), or temperature-sensitive pharmaceuticals (COL), the aircraft must have active temperature control systems. These holds can maintain a specific, consistent temperature range (e.g., +2°C to +8°C or +15°C to +25°C), which is a key service in modern air logistics.

Payload or Traffic Load

The term “Payload” (or “Traffic Load”) refers to the maximum weight of revenue-generating material the aircraft can carry. This is the sum of all cargo, mail, and baggage. Understanding payload involves two fundamental concepts:

Maximum Take-Off Weight

Every aircraft has a maximum certified weight it can safely achieve for take-off. This limit includes the aircraft itself (empty weight), the fuel, and the total payload. The maximum payload is often restricted by one of two factors:

- Weight Limit: The absolute structural limit the aircraft can physically lift and carry.

- Volume Limit: The amount of physical space available within the holds.

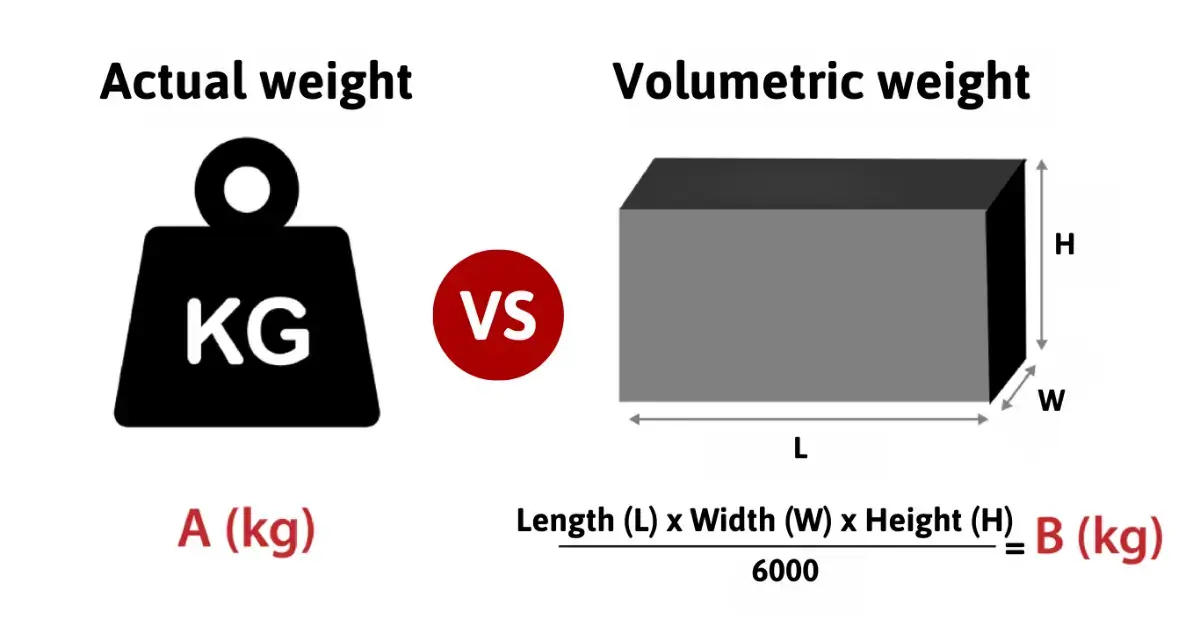

The density challenge: Volumetric weight vs. actual weight

This is where many newcomers to logistics face a learning curve. Airlines charge based on the chargeable weight, which is the greater of two values:

- Actual Gross Weight: The physical weight of the cargo in kilograms or pounds.

- Volumetric (Dimensional) Weight: A calculated weight based on the dimensions of the package.

Conclusion: turning knowledge into competitive advantage

The cargo aircraft is a marvel of engineering, built to conquer distance and time. By mastering this core knowledge-understanding the difference between a narrow-body and a wide-body, respecting the contour limits of a compartment, and calculating volumetric weight accurately-you transition from a simple service user to a strategic logistics partner. This insight allows you to choose the right aircraft for your cargo, negotiate better terms, and, most importantly, ensure that your shipment arrives on time, safely, and efficiently anywhere in the world.